Just Enough JavaScript

It can be confusing understanding what you need to know about JavaScript to be effective with TypeScript. But here are a few things that I think will help you get started.

We are going to talk exclusively about using JavaScript in a web browser environment. There are other environments where JavaScript runs, like Node.js, but we won’t be covering those here.

We’ll try to be clear in the code examples about what is JavaScript and what is TypeScript, but it’s actually pretty easy to tell the difference. TypeScript is just type annotations.

Getting JavaScript to the Browser

Section titled “Getting JavaScript to the Browser”There are a few ways to get JavaScript code to run in a web browser. The most common way is to include a <script> tag in your HTML file that contains some JavaScript code to run. For example:

<!DOCTYPE html><html lang="en"><head> <meta charset="UTF-8"> <meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1.0"> <title>Document</title></head><body> <h1>My App</h1> <script> console.log("Hello, World!"); </script></body></html>When the browser loads this HTML file, it will execute the JavaScript code inside the <script> tag.

You can also load the code stored in an external script file like this:

<!DOCTYPE html><html lang="en"><head> <meta charset="UTF-8"> <meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1.0"> <title>Document</title></head><body>

<script src="src/script1.js"></script> <script src="src/script2.js"></script> <script> console.log(userName); console.log(greetUser()) </script></body></html>var userName = "John Doe";

function greetUser() { console.log("Hello, " + userName + "!");}var userName = "Jane Smith";

function getUser() { return userName.toUpperCase();}This is crazy because the output you’d see on your console will depend on the order in which the browser loads and executes the script files. Both of these files expose variables (var) called userName and greetUser, but the second file will overwrite the first file’s variables because they are in the global scope.

Using Modules

Section titled “Using Modules”JavaScript introduced the notion of modules in ES6 (ECMAScript 2015). Modules allow you to encapsulate code and avoid polluting the global scope. You can define variables and functions inside a module, and they won’t be accessible outside the module unless you explicitly export them.

<!DOCTYPE html><html lang="en"><head> <meta charset="UTF-8"> <meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1.0"> <title>Document</title></head><body> <script src="src/module.js" type="module"></script></body></html>import {greetUser} from './module1.js';import {userName, getUser } from './module2.js';console.log({userName});console.log({greetUser: greetUser()})console.log({getUser: getUser()})import { userName } from './module2.js';

export function greetUser() { console.log("Hello, " + userName + "!");}export const userName = "Jane Smith";

export function getUser() { return userName.toUpperCase();}In this example, our browser (in the index.html) has a reference to one script file, with the type="module" attribute. This tells the browser to treat this script as a module. That module imports the other two modules.

The other modules export only the values it wants to make available to other modules.

Nothing is in the global scope. (note: I switched from var to const and let because they have block scope, which is generally preferred over function scope, more later).

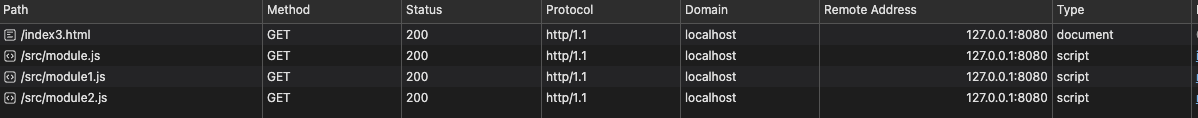

This means, though, that the browser needs to request 4 files from the server.

- The

index.html - The

module.js - The

module1.js - The

module2.js

Networks, Parsing, Cache-Busting, Bundling, Minification, All That Jazz

Section titled “Networks, Parsing, Cache-Busting, Bundling, Minification, All That Jazz”We have a few competing concerns here:

- Everything the application needs has to be downloaded over the network.

- If something hasn’t changed, we don’t want to download it again.

- We don’t want to download things that the application doesn’t need.

- We want to write our code for other humans to read, but we want the browser to download the smallest amount of code possible.

While over an HTTP/2 or HTTP/3 connection, the overhead of multiple requests is minimal, it is still not zero. And if you are on an HTTP/1.1 connection, the overhead can be significant. We like the developer experience of having multiple files (if for no other reason than to minimize merge conflicts when working in a team).

Bundling

Section titled “Bundling”We can selectively bundle our code into a smaller number of files. This is often done by a build tool like Webpack, Rollup, or Vite. These tools can analyze your code and determine which modules are used by which other modules. They can then create a smaller number of files that contain only the code that is actually used by the application.

The downside of this is that if any of those files change, the entire bundle has to be downloaded again.

Minification

Section titled “Minification”We can also minify our code. This is the process of removing all unnecessary characters from the code (like whitespace, comments, and newlines) without changing its functionality. This can significantly reduce the size of the code that needs to be downloaded.

For example:

// This is a function that greets a user with a friendly message// Note: HR condemns using gendered terms in greetings, etc.// TODO: We should probably come up with a better way to identify our website!export function greetUser(userName) { // Using a template string to create the greeting message here. return `Hello, ${userName}! Welcome to our website.`;} export function greetUser(x) { return `Hello, ${x}! Welcome to our website.`; }Tree Shaking

Section titled “Tree Shaking”We can also use a technique called tree shaking to remove unused code from our bundles. This is done by analyzing the code and determining which modules are actually used by the application. Any modules that are not used can be removed from the bundle. Some tree shaking can also remove unused exports from modules.

Tree shaking works best with exported values and functions. It can’t do too much with exported classes, though. For example, if you import a class that has 32 methods on it, tree-shaking will not be able to remove any of those methods, even if you only use one of them.

Cache Busting

Section titled “Cache Busting”When we bundle, minify and treeshake our code, the browser still needs to download the file before it can be parsed and executed in the browser. If the file has changed, the browser needs to download the new version of the file.

The HTTP specification says that responses should include a Cache-Control header that tells the browser how long it can cache the file. It’s a way of telling the browser that “hey, if you already have a copy of this file (/src/module.js), you can use that copy for the next 24 hours, or year, or whatever, and you don’t need to download it again”.

But what if the file changes? What if we need the user to use the latest version of the file?

Caching is based on the URL of the file. If the URL changes, the browser will download the new version of the file. This is where cache busting comes in. We can change the URL of the file whenever it changes.

One common way to do this is to include a hash of the file’s contents in the filename. For example, instead of /src/module.js, we might use /src/module.abc123.js, where abc123 is a hash of the file’s contents. If the file changes, the hash will change, and the URL will change, so the browser will download the new version of the file.

You’d also update the reference in your HTML file:

<script type="module" src="/src/module.abc123.js"></script>This way, you can set a long cache duration (like one year) for your files, and the browser will only download a new version of the file when it actually changes. This is a common technique used by build tools like Webpack, Rollup, and Vite to ensure that users always have the latest version of the files they need.

Parsing and Execution

Section titled “Parsing and Execution”In the use of something like Angular1 or other so-called “Singe Page Applications” (SPAs), the entire application is downloaded to the browser when the user first visits the site. This can be a large amount of code, and it can take a long time to download, parse, and execute.

There are a lot of variables here that will impact how soon the application is usable by the user. The size of the code, the speed of the user’s internet connection, the performance of the user’s device, and many other factors can all impact how soon the application is usable.

Our goal should be to have a single bundle that is as small as possible, and that can be downloaded, parsed, and executed as quickly as possible. This is often referred to as the “Time to Interactive” (TTI). It can eventually use other bundles that are downloaded (either in the background, or on demand), but the initial bundle should be as small as possible.

So we like to end up with multiple bundles of JavaScript code to send to the browser. The initial bundle should be as small as possible, and it should contain only the code that is necessary to get the application up and running.

Factoring your other bundles so that they can be loaded on demand (for example, when the user navigates to a different part of the application) can help reduce the initial bundle size. This is often done based on “temporal boundaries”, meaning:

- Code that is needed rarely (like an Admin panel) should be in a separate bundle that is only loaded when the user navigates to that part of the application.

- Code that is needed for a specific feature (like a chat widget) should be in a separate bundle that is only loaded when the user uses that feature.

- Code that is needed for a specific route (like a specific page) should be in a separate bundle that is only loaded when the user navigates to that route.

- Code that is needed for a specific user role (like an Admin) should be in a separate bundle that is only loaded when the user has that role.

- Code that is needed for a specific device (like a mobile device) should be in a separate bundle that is only loaded when the user is on that device.

- Code that has a high frequency of change (like a library that is updated frequently) should be in a separate bundle.

Footnotes

Section titled “Footnotes”-

Angular also has the ability to pre-render the application on the server, which can significantly improve the TTI. This is often referred to as “Server-Side Rendering” (SSR) or “Universal” rendering. This is a more advanced topic, and we won’t be covering it in this course. ↩